Your jetlagged correspondent--marketing and publicity manager--Esther Kim gulped gallons of white coffee this past weekend and went forth to explore the annual George Town Literary Festival (GTLF) in Penang, Malaysia. She arrived from New York two days prior to the festival’s start. Despite the time difference between Brooklyn and George Town, essentially night and day, she found the literary festivity and political urgency also provided the much needed jolt of energy to keep her eyes wide open, if not ajar.

Here are some of her notes from the weekend:

For its 7th annual gathering, the GTLF revolved around the theme ‘Monsters and (Im)mortals’. Last year the festival welcomed the likes of our own Prabda Yoon.

George Town is a northern city situated on the island of Penang, which proudly boasts a reputation as a ‘rebel state’ as well as home to the best street food in Malaysia. A UNESCO heritage site, traces of the bustle of migrants, traders, merchants, and sailors are still felt in the cooking, the lovingly preserved teahouses and worn shop signs. With the three coinciding festivals (Literary, Jazz, and Inbetween) and the marathon this weekend, the city it most strongly reminded me of was Edinburgh...

I arrived late on Friday evening, missing the day’s translation-centered panels, but in time to hear the opening ceremony remarks by Bernice Chauly, Festival Director, who introduced Lord Fox, a trio from Glasgow, Scotland. They performed a sinuous and haunting poem about a murderous prince bent on seducing his next victim, Lady Mary. It set the tone for some of the mythic, darker elements of the festival and its excavations of power, disguise, and reversals. The festival theme ‘Monsters and (Im)mortals’ was elastic enough to include a range of free panels--from hard political analysis of the nation-state and demagogues to literary excavations of ‘Caliban,’ ‘Utopia’ or my fave ‘Braver Worlds’.

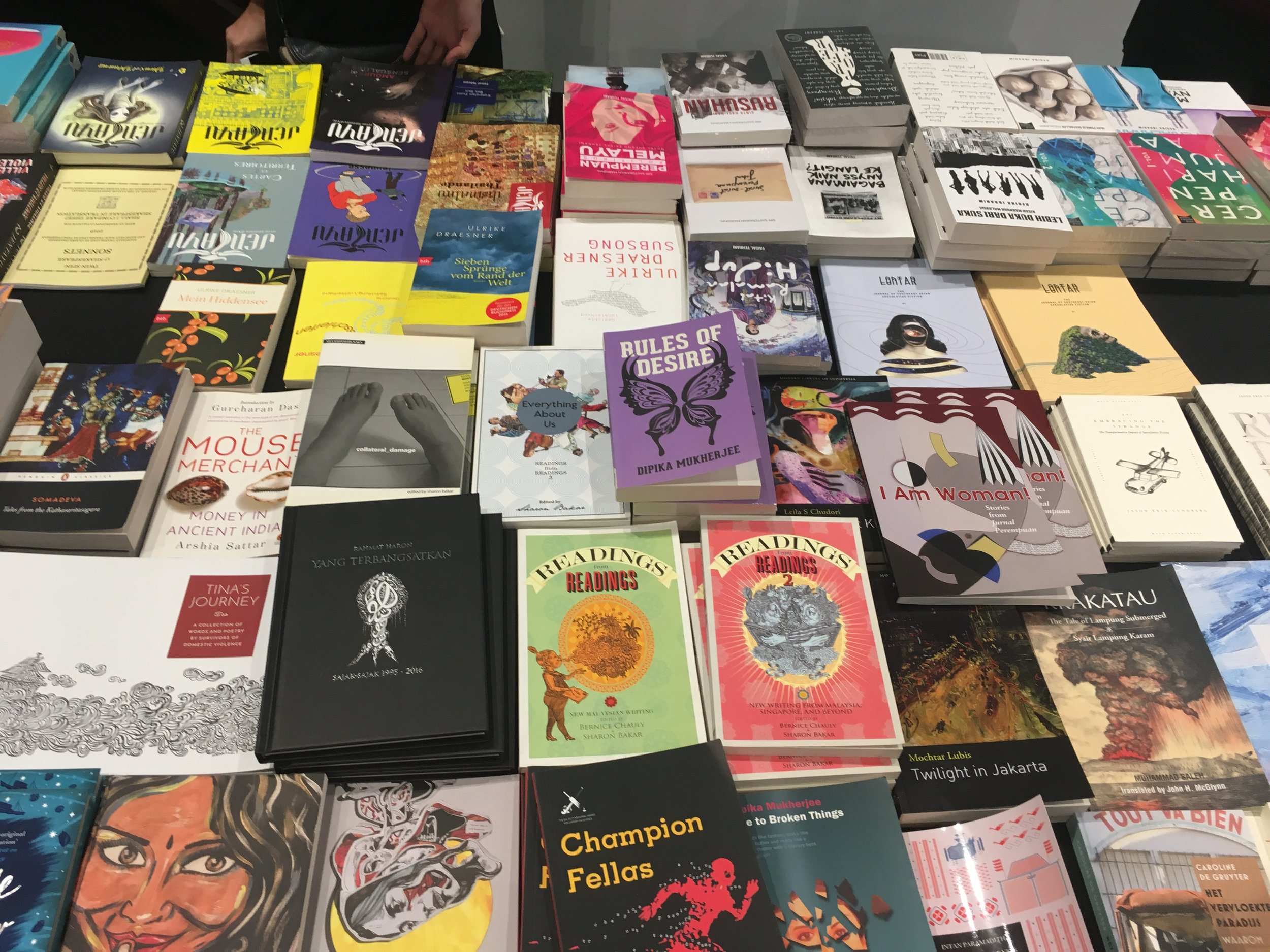

Indie Gerakbudaya - Penang was the sole bookseller, and they brilliantly curated the selection for sale by the food stands. Nope, I didn’t hoard their bookmarks, why d’you ask?

Book haul from Gerakbudaya

My favorite discussion of all was probably ‘Braver Worlds’, a fantastic and rare all-female (!) panel on speculative fiction. Malaysian fantasy writer Zen Cho, Hong Konger surrealist author Dorothy Tse, Indonesian horror writer Intan Paramaditha, and Malaysian crime writer Felicia Yap each read aloud from their books and batted around questions on their chosen genres and challenges. The conversation was moderated by Singaporean press Epigram’s editor Jason Lundberg, who defined ‘speculative fiction’ as an umbrella term that encompasses narrative fiction with supernatural or futuristic elements. Though the panel was all female and Asian, each author, of course, had distinct roads to publication as they worked within different genres, languages and national / economic structures.

In response to questions on their preference for ‘speculative fiction’ over ‘realism’, Dorothy Tse noted, ‘A realistic story is not real but just one kind of reality. Even now we are bounded by the language we know and the story we are told by the media.’

Later Tse mentioned how the next novel she’s currently working on--about a shy professor who falls in love with a door--addressed Hong Kongers tendency to avoid intimacy and to be overly polite. To illustrate the latter, she mentioned how a few of her students wrote her during the Umbrella Revolution, requesting permission to skip class to protest. ‘You’re protesting! Why are you asking me for permission?!’

Over in poetry, there were two standouts. First, the iconic Malay modernist poet and painter Latiff Mohidin made a rare public appearance at the festival. He read several poems in the Malay original, and the indefatigable festival co-curator Pauline Fan followed with the English translations by Eddin Khoo (forthcoming publication). Mohidin discussed his painting, his poetry, and his translation work with Fan, who translates herself from German to Malay.

On his poetry: ‘There are actually three ducks but only two are represented.’

On his translation of Faust from German to Malay, he laughed at his naivety in tackling the project. ‘I don’t know why I picked Faust! It’s a very heavy book. Took me about four years.’ ‘There were two words in German I couldn’t find the right words for in Malay. I stayed up sleepless for four nights trying to figure out those two words.’ Originally published by DBP (Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka) in the ‘60s, his works are now out of print, so the English translation by Eddin Khoo marks a brilliant effort to reignite the availability and interest in Mohidin’s work.

Earlier, the sublime poetry panel explored the power of poetry to transcend the limits of mundane human life, through the ideal of the ‘sublime’. Panelists wrestled with Adorno’s famous claim ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’. To which poet James Shea countered with Celan’s ‘After Auschwitz, only poetry’. Avant-garde, experimental poet Takako Arai immediately centered the question on the recent natural disaster in Japanese memory, the March 2011 tsunami / earthquake. She recalled how in the face of the disaster, the government began TV broadcasting instead of commercials. Contemporary female poet Kaneko Misezu was played on repeat. Perhaps then poetry was solace. Perhaps then poetry was insufficient.

She then read in English from her poem ‘Give Us Morning,’ translated from the Japanese by Jeffrey Angles, which repeatedly invokes Amaterasu, the sun goddess. She spoke, too, on the fascinating difference between the Japanese and English versions, stating that in Japanese the subject is abbreviated from the sentence structure. Arai said, 'My translator had to fill in the subject in the translation, and I was surprised when reading the English version because in the Japanese version it was unclear who the speaker was--everything was covered in translucent fabric. But Jeffrey’s translation pulled the fabric aside, so it was clear who said what and what direction they were looking. In that sense, the dance of the female deity was more active in the English version.'

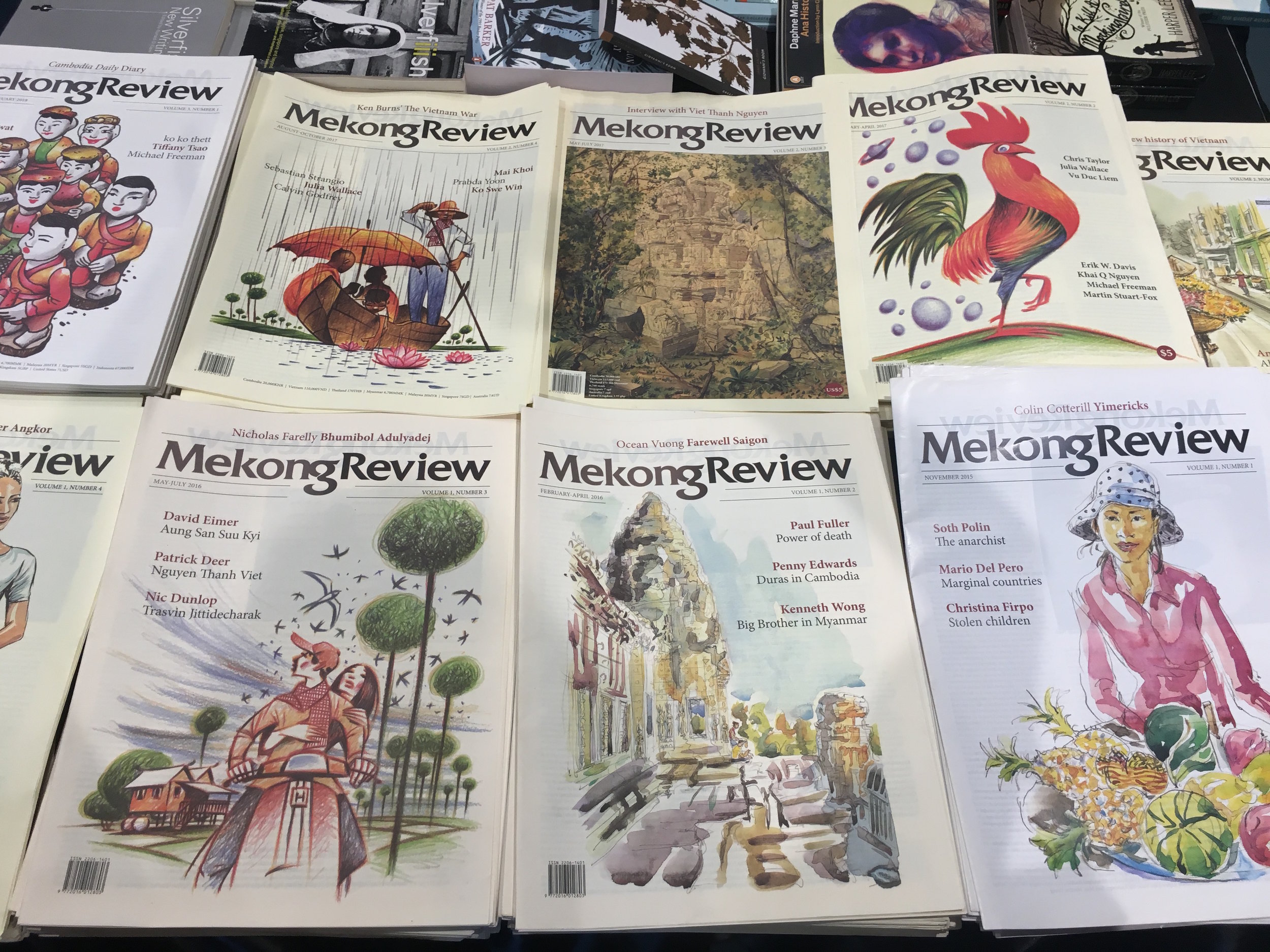

Last but not least, the panel on the return of print regional magazines explored the past, present, and future of the hard-copy. This spirited panel moderated by Gareth Richards, co-curator of the festival, former academic and current owner of indie bookstore Gerakbudaya Penang, featured Minh Bui Jones of Mekong Review, Michael Vatikiotis formerly of Far Eastern Economic Review, and Gwen Robinson of Nikkei Asian Review. Mekong is a young, new and excellent publication that fills a clear need within Southeast Asia with its beautiful photography and long-form cultural reviews. Founder Minh Bui Jones waxed poetic about the beauty of print and Mekong’s decision to go with the tabloid format (like the London Review of Books). Vatikiotis spoke about the rise and fall of the Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER), a behemoth, which was in print from 1946-2004. The first of its kind, FEER was a magazine for the region and covered the formation of today’s nation-states and what neighboring countries that barely knew each other were up to. Before it folded, it had a very fine culture section--Ian Buruma, the current editor in chief of the New York Review of Books, was its first head.

Next year, George Town Literary Festival promises to expand to include more Malay writers and translators and extend to four days of programming. Part of a growing trend in Asia-Pacific literary festivals, including the Brisbane Writers Festival, Melbourne Writers Festival, Dhaka Literary Festival, Jaipur Literature Festival, Singapore Literary Festival, and Ubud Writers and Readers Festival, GTLF boldly charges forward to engage the multiplicity of languages and communities in Southeast Asia and slyly subvert official histories.